The

English Civil War fought between 1642 and 1646, was a mobile

war with rival armies forever on the move. This war did not

consist of one or two major battles to decide the issue but

continued for four years with sieges, skirmishes, small and

very large battles ranging from the distant north to the

far south west of England. large battles ranging from the distant north to the

far south west of England.

Stow-on-the-Wold lies on the junction of

eight roads so consequently both the royalist and parliamentary

armies frequently passed through the town. In 1644, King

Charles, on route to Evesham, passed through with a small

army. In hot pursuit was a larger parliamentary army under

the command of Sir William Waller who went on to Winchcombe.

The king came back through Stow-on-the-Wold a few days later,

on his way to Witney again followed by Waller. One wonders

what the inhabitants of Stow made of all this.

King Charles I came to Stow for a third

time just before the battle of Naseby in 1645. This time

he stayed the night, taking lodgings at the inn in the lower

corner of the square now called The King’s Arms. His

army camped along the Maugersbury road. After Naseby, Lord

Fairfax, leading parliamentary forces passed through Stow-on-the-Wold

on their way to Lechlade. It would only be a matter of time

before these rival armies arrived in Stow-on-the-Wold at

the same time. In March 1646, they did and this time Stow-on-the-Wold

would provide the setting for the last battle of the English

Civil War.

Despite the defeat of the Royalist army

at Naseby the king still thought he could overthrow the parliamentary

forces if he could gather the surviving royalist forces from

the West Midland and Welsh borders and get them to his base

in Oxford. The task of gathering the remaining soldiers and

marching them back to Oxford fell to Sir Jacob Astley.

Parliamentary forces soon had news of Astley’s

return march and started to converge on them from Gloucester,

Evesham, Hereford and Lichfield. The parliamentary army under

the command of Colonel Thomas Morgan blocked Astley’s

attempt to cross the River Avon at Evesham and several days

were spent marching and counter-marching. Morgan withdrew

to Chipping Campden in the hope that Astley would cross the

river and then engage him in battle. Astley eventually crossed

at Bidford-on-Avon and marched through Broadway before climbing

Fish Hill. Morgan did not attack as he was waiting for re-enforcements

from Lichfield and he allowed Astley to pass by. Information

reached Morgan that the royalist army was to be joined by

cavalry sent by the King from Oxford so when his re-enforcements

finally arrived he decided to attack.

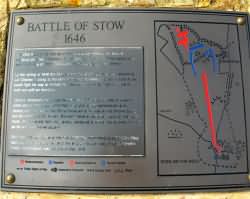

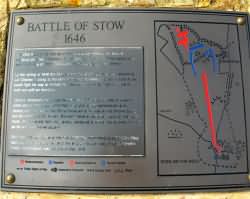

Before dawn on the 21st March, Morgan’s reconnaissance found Astley’s army drawn up in battle

order on high ground close to the village of Donnington about

1½ miles north of Stow-on-the-Wold. As soon as it

was light, Morgan attacked up the hill but his left wing

were driven back in confusion and then overpowered. At first

victory seemed doubtful. Morgans’s right wing of cavalry pressed the attack and successfully routed the royalist cavalry who left the field. In the centre, the royalist forces held their ground against the parliamentary attack, which was forced to withdraw. Before dawn on the 21st March, Morgan’s reconnaissance found Astley’s army drawn up in battle

order on high ground close to the village of Donnington about

1½ miles north of Stow-on-the-Wold. As soon as it

was light, Morgan attacked up the hill but his left wing

were driven back in confusion and then overpowered. At first

victory seemed doubtful. Morgans’s right wing of cavalry pressed the attack and successfully routed the royalist cavalry who left the field. In the centre, the royalist forces held their ground against the parliamentary attack, which was forced to withdraw.

A second parliamentary advance followed and this time the royalist forces were pushed back in the

direction of Stow. Fighting continued into the Square and local legend tells that blood flowed down Digbeth Street such was the slaughter. Fighting in the town ended with the capture of Astley. A drum was brought for the royalist commander to sit and rest on; he was after all sixty-six years old and a true veteran of over forty years military service. He was clearly able to see the finality and the significance of this battle because he said to his captors:

'Gentlemen, ye may now sit down and play,

for you have done all your Worke,

if you fall not out among yourselves!’

These prophetic words described the years

that were to follow as people struggled to define a future

role for parliament and the crown.

After the battle, the royalist prisoners

were held overnight in St. Edward’s Church because

it was the most secure building in the town and large enough

to hold such a number. The dead were laid in Digbeth Street,

which re-enforces the legend of blood flowing down the road.

To this day, their burial site remains a mystery.

Subsequently the prisoners were marched

to Gloucester and after further confinement; they were exchanged

for parliamentary prisoners or released on oath not to take

up arms again.

Sir Jacob Astley was imprisoned in Warwick

Castle until his release in June when Oxford surrendered

to parliamentary forces. He eventually retired to his family

house in Kent after a long and most eventful life. He died

in 1652 at the age of 72.

Colonel Thomas Morgan saw service in Scotland

and was promoted to the rank of major-general. He fought

in Flanders and was involved in the war with Holland when

he became governor of Jersey. He died in 1679, a fine soldier

who had served parliament and his country well.

In April King Charles I, realising his cause

was lost, slipped away in disguise from Oxford and surrendered

at Newark. In April King Charles I, realising his cause

was lost, slipped away in disguise from Oxford and surrendered

at Newark.

So, in and around this hill top town of

Stow-on-the-Wold was fought the last battle of the English

Civil War which was ultimately to lead to the execution of

the king and to lay the foundation of our parliamentary democracy.

Less than half a mile to the west of Donnington,

on a pubic footpath, stands a stone obelisk marking the sight

where the Royalist forces spent the night before the battle

and where they drew up to defend themselves. It is plain

to see the commanding position they held and the difficult

slope the parliamentary army had to climb in order to dislodge

them.

Today a simple stone stands in the churchyard

of St Edward’s Church, Stow-on-the-Wold, to honour

all those men who fought and died for their beliefs. |